Introduction

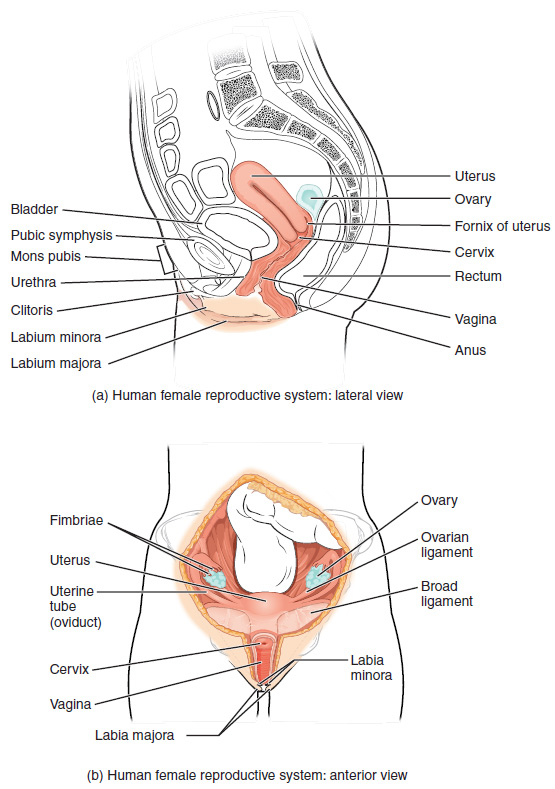

The uterus is positioned between the bladder and the rectum in the pelvis and is the central anatomical landmark of the female reproductive system.1-4 It is described as having a pyriform, or "inverted pear" shape, and is a thick, muscular, hollow organ weighing 30-40 grams and is approximately 7.5 centimetres in length (see Figures 1-3).1-3,5-9

Gross Anatomy

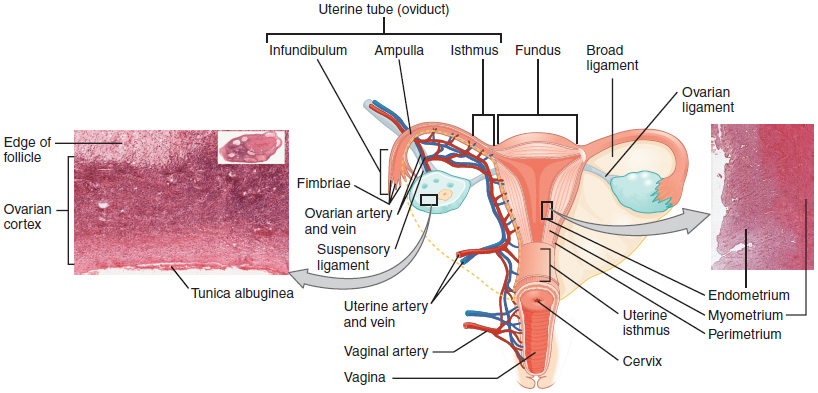

The uterus can be divided into four separate areas: the fundus, the body, the isthmus, and the cervix (see Figures 1).

The uterine tubes open into the superolateral angles of the uterus, one on each side, and above this point is the fundus.1,2 The superolateral angle where the uterine tube opens into the cavity of the uterus is called the cornu.1 Below the entrance of the uterine tubes is the uterine body which is the central part of the uterus which narrows inferiorly until it reaches a constriction called the isthmus.1,2 Below the isthmus is the cervix.1,2

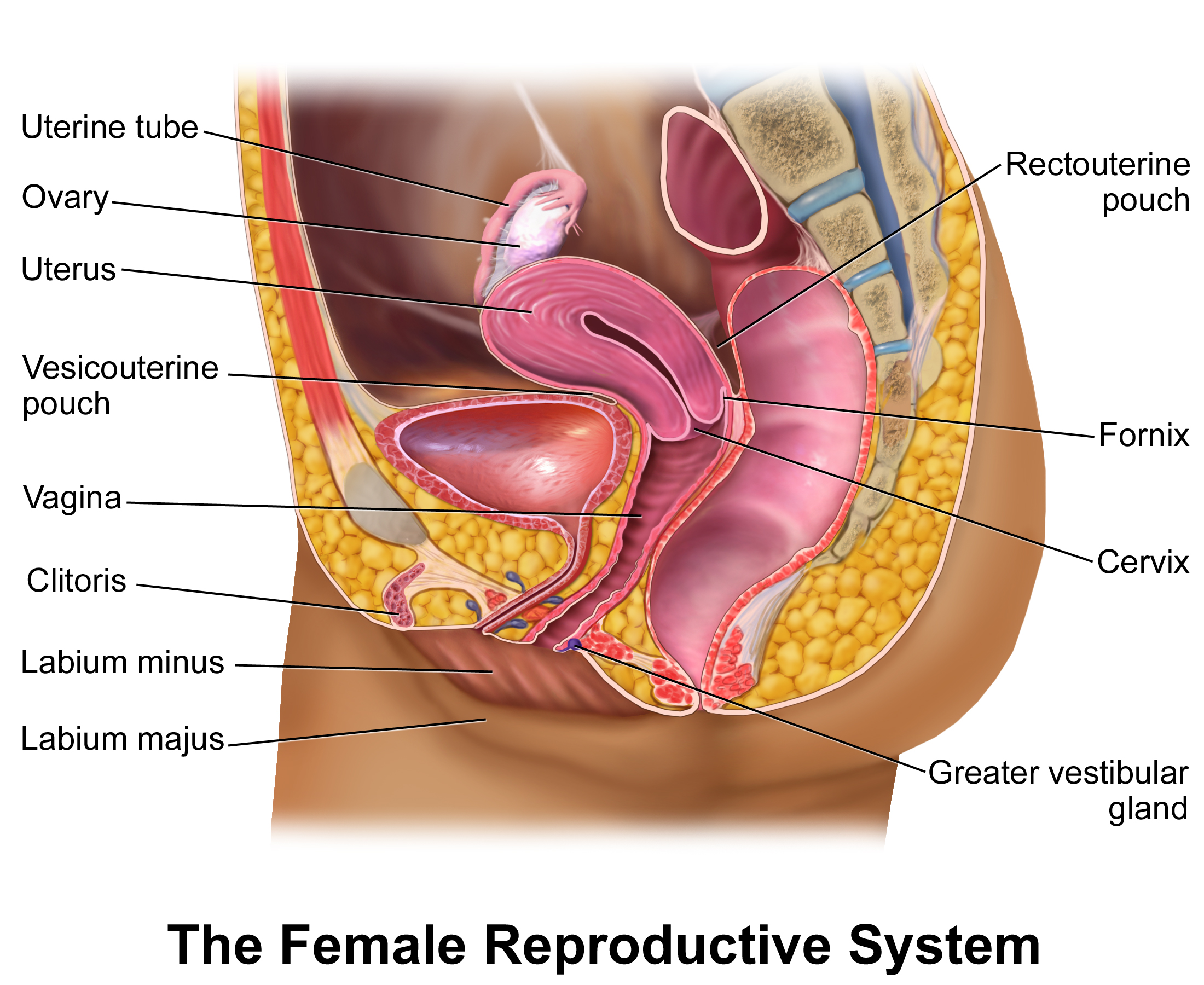

The uterus is an extraperitoneal organ.1 Anteriorly, peritoneum covers the uterus from the fundus to the level of the isthmus before reflecting onto the bladder forming the vesicouterine pouch.1,2,5 This anterior peritoneum is only loosely adherent allowing for distension of the bladder.5

Posteriorly, the peritoneum continues from the fundus to cover the cervix and posterior fornix of the vagina before reflecting onto the anterior surface of the rectum forming the rectouterine pouch, also called the pouch of Douglas.1,2 Additionally, two crescenteric folds of peritoneum, named rectouterine or sacrogenital folds, pass on either side of the rectum from the cervix to the posterior wall of the pelvis which bound the rectouterine pouch laterally.2 The rectouterine pouch is the lowest part of the peritoneal cavity so is a common site of fluid collection.2

Internally, the cavity of the uterus is triangular in the coronal plane narrowing towards the internal os of the isthmus. The cavity continues to communicate with the vaginal vault through the external os.1,2,5

Changes with Development

Throughout life, the size of the uterus changes. In children, the cervix is double the size of the uterus body, whereas during reproductive age the body is bigger than the cervix.4,5 After menopause the uterus becomes atrophic and the body is again smaller than the cervix.4

Layers of the Uterine Wall

The thick wall of the uterus is divided into three main layers: the peritoneum, the myometrium, and the endometrium.1,3

The outer layer, the peritoneum, covers the uterus as described above. The myometrium is the muscular middle layer of the uterus.1 The innermost layer, the endometrium, is divided into two: the stratum basalis and the stratum functionalis.1,3 The stratum functionalis is the innermost layer and is shed during menstruation and is regenerated from the stratum basalis, a permanent layer.1,3

Positioning

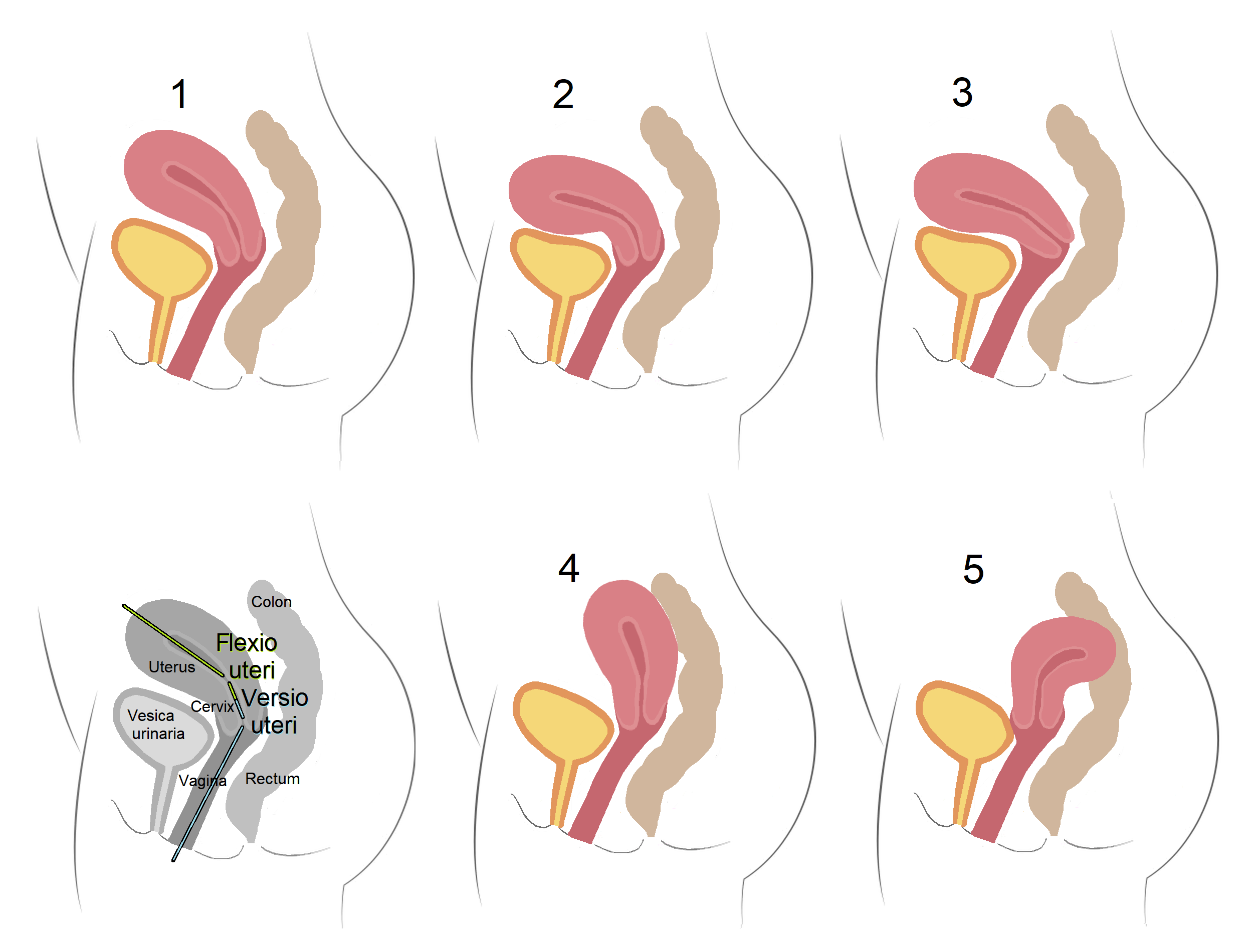

The commonest position of the uterus is in an anteverted-anteflexed position1,3,4

There can be variation in the positioning of the uterus from the typical anteverted-anteflexed position (see anatomical variation section below).

Relations

Anterior to the uterus is the vesicouterine pouch and the bladder.1,2,5

Posteriorly is the rectouterine pouch (pouch of Douglas), the rectum, and often the ovaries can prolapse down into the rectouterine pouch.1,5

Laterally are the broad ligaments which are described in more detail in a separate article.

Blood Supply and Innervation

Blood Supply

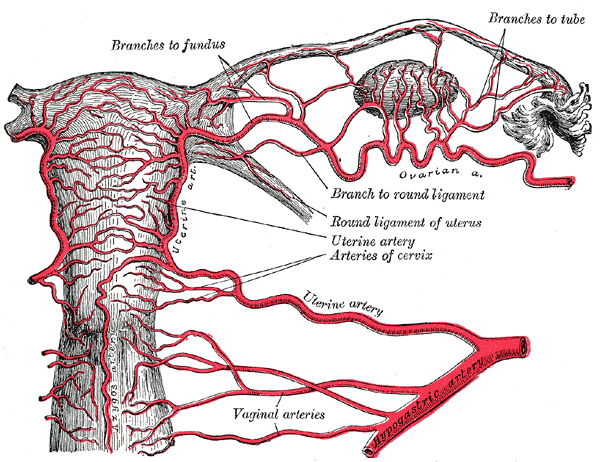

The uterus has a dual artery supply: the uterine artery and the ovarian artery.1,2,4

The major supply is from the uterine artery which originates from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery.1,3 The ovarian artery arises from the abdominal aorta2 and anastomoses with the uterine artery within the broad ligament.3 As the uterine artery penetrates deeper into the layers of the uterus it gives off arcuate arteries, radial arteries, and finally spiral arteries which supply the endometrium.1,4

The uterine vein follows the course of the uterine artery and is larger in size. It drains blood into the internal iliac vein.1-3,5

Innervation

The uterus receives innervation from the inferior hypogastric plexus, namely the uterovaginal plexus.1,2,4 It receives parasympathetic innervation from the pelvic splanchnic nerves.1,4

Lymphatic Drainage

The fundus of the uterus, along with the uterine tubes and ovaries, drain into para-aortic lymph nodes.1,3,5

The body and cervix drain into internal and external iliac lymph nodes, with some lymphatics travelling with the round ligament to drain into the superficial inguinal nodes.1,4

Anatomical Variations

Physiological variation of the uterus can occur with age as described above. There can also be variations in the position of the uterus which differs from the typical anteverted-anteflexed position as shown in Figure 6.12 Retroversion refers to the angle between the vagina and cervix facing posteriorly and retroflexion refers to the angle between the cervix and uterine body facing posteriorly.6

Müllerian anomalies are when there is incomplete development of the female reproductive tract which can lead to a variety of anatomical variations.4 The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) classifies Müllerian anomalies into nine categories, updating the old 1988 American Fertility Society (AFS) classification in 2021.13 The nine categories are:

This interactive tool from the ASRM helps explain the anomalies in more detail.13

Anatomical Variations

In previous RANZCR exam papers (accessible here candidates have been required to:

While this article provides details on the overall anatomy, as well as the lympahtic drainage of the uterus, the ASRM interactive tool provided above is a good resource for understanding the anatomical variants in more depth.